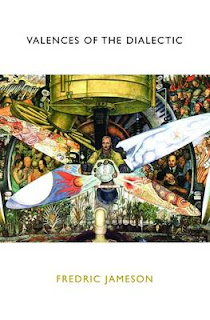

Fredric Jameson’s Valences of the Dialectic is a book that is very similar to Archeologies of the Future. They are both massive tomes, comprised in part of new material and republished essays, that represent sustained meditations on the central and enduring concepts of Jameson’s thought, namely Utopia and Dialectics. Beyond such superficial resemblances they also function together. If the earlier book on utopia revealed something a dialectic of the very presentation of utopia itself, in which the later cannot be separated from its negation, from dystopia, then the latter reveals a utopian dimension of the dialectic itself: the goals of the dialectic, overcoming reification and the static binary between self and society, are inseparable from utopia, from a transformation of social conditions. This last point, which constitutes not so much a new position on the part of Jameson, but a new articulation of existing themes and problematics (after all, the essays in question go back over twenty years) will have to wait for a later post, after I finish the book on the dialectic.

At this point I would like to approach Valences of the Dialectic rather obliquely, from what it says about the more or less current conjuncture. Given that Jameson is most famous for describing “postmodernism” as the cultural logic of late capitalism it makes sense to ask where we stand now with respect to capitalism, late, resurgent, or dying, and its specific cultural logic. There are two statements that appear more than once in Jameson’s book, albeit in different formulations.

The first describes the present as a simplifying of the ideological dimension. As Jameson writes:

“What is paradoxical is that the crudest forms of ideology seem to have returned, and that in our public life an older vulgar Marxism would have no need of the hypersubtleties of the Frankfurt School and of negative dialectics, let alone of deconstruction, to identify and unmask the simplest and most class conscious motives and interests at work, from Reaganism and Thatcherism down to our own politicians: to lower taxes so rich people can keep more of their money, a simple principle about which what is surprising is that so few people find it surprising anymore, and what is scandalous, in the universality of market values, is the way it goes without saying and scarcely scandalizes anyone.”

One could see this as a much delayed fulfillment of Marx’s statement in The Communist Manifesto, where Marx argues that capitalism entails a reduction of ideology to its material base. All the illusions of religion and monarchy fall aside and “man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real condition of life and his relations with his kind.” The major exception being that in Marx’s account this clarity is the catalyst for revolution, while Jameson suggests that it is met with a shrug. We all know that the rich pass laws in their interest, and the best we can hope to do is to one day become rich so that we might do the same. Jameson could be describing a kind of universal cynicism that is synonymous with the post-modern condition.

However, the second description of the present suggests something else entirely. As Jameson writes in an often repeated formula:

“The dualism of culture and the economic has however come to seem unproductive, particularly in the third stage of capitalism (postmodernity or late capitalism), in which these two dimensions have seemed to dedifferentiate and to fold back in on each other: culture becoming a commodity and the economic becoming a process of libidinal and symbolic investment.”

On first glance one could say that this second statement contradicts the first, but that seems almost silly given that both of these statements come from a book on dialectics. However, the second does complicate the first. It is no longer that the economy, and with it the interests of class, emerges from an ideological cloud, but that the economy becomes its own kind of ideology (Think of the proliferation of investing magazines and television shows, aimed less at informing an invest class than produce this “economy as culture’). The trajectory of these two remarks follows Marx’s own trajectory from the Manifesto to Capital, from the holy that is profaned to the misty enshrouded realm of commodity fetishism.

Two provisional conclusions:

We are living in an age in which the category of ideology is increasing inadequate. This is not because it is metaphysically suspect, as Foucault and others claimed, but because it no longer adequately grasps the way society functions. One of the things that I like about the first quote is that it demonstrates that what is theoretically sophisticated is not necessarily political useful (a difficult lesson, and one coming from an odd place). However, the second quote points to the fact that this is not an “end of ideology,” but that new critical concepts are needed to make sense of this new order.

Second, and this is much more provisional, I think that understanding the combination of cyncism and libidinal investment in the economy might help explain the peculiarities of the current situation. We are cynical about capital's capacity to deliver any kind of just order, yet invested in it all the same. Zombie capitalism: desire lingering on, long after its rational has ceased.

Photo of Randall Park Mall, Cleveland, Ohio.

Photo of Randall Park Mall, Cleveland, Ohio.

2 comments:

Jason, I really enjoyed your posting on Sohn-Rethel--really nicely written, but I don't know enough about him to comment on the content. In terms of _Valences_, apparently at the last utopian studies conference Fred talked about the inability of the Left to imagine a utopia beyond capitalism, that they are all really dystopias (nostalgic or regressive). I think that the utopian dimension of his work has often been overlooked, and I'm glad to see it more blatantly move to the forefront of his public persona. If this book is in dialogue with _Archeologies_, then the second book, _The Modernist Papers_ is a complement to _A Singular Modernity_, though I think that that book is more successful. Indeed, it is as yet unclear to me if this current series is of a piece, footnotes to earlier monographs, or sketches for a new larger project. Certainly, as you write, how it signals changes in his thinking about fundamental ideas is exciting.

I live near Cleveland and I did go that mall once. Scary stuff. To see people so reticent about the prospect of revolution does not seem to me to be any kind of inherent reaction, but one that has resulted from systematic attacks upon Marxists. I have seen in people a general lowering of standards of success, but also, I live near Cleveland, which has been decimated post-NAFTA, with recent economic conditions being of little help either, but I know this city is not unique. What I would like to discuss at one point, and have thought about lately, is peoples' views on what is ethical in such a state of affairs and a conversation on what are the dominant societal interactions of people across the US. I'm thinking back to your blog entry on Inception, but I still wonder what the implications of this public/private collapse are, which puts power over the public life of the individual under the purview of the employer. All I can seem to think of is an absurdist gaiety in the face of a system of life destruction that we inhabit but don't control at the best. And at the worst, a soul crushing burden for all the pain and our lives cause. As for dismissal of utopianism, I see this as dismissal of prospects for collective action for a collective good.

Post a Comment